Brouwer fixed-point theorem

Brouwer's fixed-point theorem is a fixed-point theorem in topology, named after Luitzen Brouwer. It states that for any continuous function f with certain properties there is a point x0 such that f(x0) = x0. The simplest form of Brouwer's theorem is for continuous functions f from a disk D to itself. A more general form is for continuous functions from a convex compact subset K of Euclidean space to itself.

Among hundreds of fixed-point theorems,[1] Brouwer's is particularly well known, due in part to its use across numerous fields of mathematics. In its original field, this result is one of the key theorems characterizing the topology of Euclidean spaces, along with the Jordan curve theorem, the hairy ball theorem and the Borsuk–Ulam theorem.[2] This gives it a place among the fundamental theorems of topology.[3] The theorem is also used for proving deep results about differential equations and is covered in most introductory courses on differential geometry. It appears in unlikely fields such as game theory. In economics, Brouwer's fixed-point theorem and its extension, the Kakutani fixed-point theorem, play a central role in the proof of existence of general equilibrium in market economies as developed in the 1950s by economics Nobel prize winners Gerard Debreu and Kenneth Arrow.

The theorem was first studied in view of work on differential equations by the French mathematicians around Poincaré and Picard. Proving results such as the Poincaré–Bendixson theorem requires the use of topological methods. This work at the end of the 19th century opened into several successive versions of the theorem. The general case was first proved in 1910 by Hadamard, and then in 1912 by Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer.

Contents |

Statement

The theorem has several formulations, depending on the context in which it is used. The simplest is sometimes given as follows:

-

- In the plane

- Every continuous function f from a closed disk to itself has at least one fixed point.[4]

This can be generalized to an arbitrary finite dimension:

-

- In Euclidean space

- Every continuous function from a closed ball of a Euclidean space to itself has a fixed point.[5]

A slightly more general version is as follows:[6]

An even more general form is better known under a different name:

-

- Schauder fixed point theorem

- Every continuous function from a convex compact subset K of a Banach space to K itself has a fixed point.[8]

Notes

The function f in this theorem is not required to be bijective or even surjective. Since any closed ball in Euclidean n-space is homeomorphic to the closed unit ball D n, the theorem also has equivalent formulations that only state it for D n.

Because the properties involved (continuity, being a fixed point) are invariant under homeomorphisms, the theorem is equivalent to forms in which the domain is required to be a closed unit ball D n. For the same reason it holds for every set that is homeomorphic to a closed ball (and therefore also closed, bounded, connected, without holes, etc.).

The statement of the theorem is false if formulated for the open unit disk, the set of points with distance strictly less than 1 from the origin. Consider for example the function

which is a continuous function from the open interval (−1,1), the one-dimensional unit disk, to itself. As it shifts every point to the right, it cannot have a fixed point. (But it does have a fixed point for the closed interval [-1,1], namely f(x) = x = 1).

Illustrations

The theorem has several "real world" illustrations. For example: take two sheets of graph paper of equal size with coordinate systems on them, lay one flat on the table and crumple up (without ripping or tearing) the other one and place it, in any fashion, on top of the first so that the crumpled paper does not reach outside the flat one. There will then be at least one point of the crumpled sheet that lies directly above its corresponding point (i.e. the point with the same coordinates) of the flat sheet. This is a consequence of the n = 2 case of Brouwer's theorem applied to the continuous map that assigns to the coordinates of every point of the crumpled sheet the coordinates of the point of the flat sheet immediately beneath it.

Similarly: Take an ordinary map of a country, and suppose that that map is laid out on a table inside that country. There will always be a "You are Here" point on the map which represents that same point in the country.

In three dimensions the consequence of the Brouwer fixed-point theorem is that no matter how much you stir a cocktail in a glass some point in the liquid will remain in exactly the same place in the glass as before you took any action, assuming that, presumably, the final position of each point is a continuous function of its original position, and that the liquid after stirring is contained within the space originally taken up by it.

Intuitive approach

Explanations attributed to Brouwer

The theorem is supposed to have originated from Brouwer's observation of a cup of coffee.[9] If one stirs to dissolve a lump of sugar, it appears there is always a point without motion. He drew the conclusion that at any moment, there is a point on the surface that is not moving.[10] The fixed point is not necessarily the point that seems to be motionless, since the centre of the turbulence moves a little bit. The result is not intuitive, since the original fixed point may become mobile when another fixed point appears.

Brouwer is said to have added: "I can formulate this splendid result different, I take a horizontal sheet, and another identical one which I crumple, flatten and place on the other. Then a point of the crumpled sheet is in the same place as on the other sheet."[10] Brouwer "flattens" his sheet as with a flat iron, without removing the folds and wrinkles.

One-dimensional case

In one dimension, the result is intuitive and easy to prove. The continuous function f is defined on a closed interval [a, b] and takes values in the same interval. Saying that this function has a fixed point amounts to saying that its graph (black in the figure on the right) intersects that of the function defined on the same interval [a, b] which maps x to x (green).

Intuitively, any continuous line from the left edge of the square to the right edge must necessarily intersect the green diagonal.

It is not hard to give a formal proof. It suffices to consider the function g which maps x to f(x) - x. It is ≥ 0 on a and ≤ 0 on b. By the intermediate value theorem, g has a zero in [a, b]; this zero is a fixed point.

Brouwer is said to have expressed this as follows: "Instead of examining a surface, we will prove the theorem about a piece of string. Let us begin with the string in an unfolded state, then refold it. Let us flatten the refolded string. Again a point of the string has not changed its position with respect to its original position on the unfolded string."[10]

In one dimension, Brouwer's fixed point theorem is equivalent to the intermediate value theorem.

History

The Brouwer fixed point theorem was one of the early achievements of algebraic topology, and is the basis of more general fixed point theorems which are important in functional analysis. The case n = 3 first was proved by Piers Bohl in 1904 (published in Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik). It was later proved by L. E. J. Brouwer in 1909. Jacques Hadamard proved the general case in 1910, and Brouwer found a different proof in 1912. Since these early proofs were all non-constructive indirect proofs, they ran contrary to Brouwer's intuitionist ideals. Methods to construct (approximations to) fixed points guaranteed by Brouwer's theorem are now known, however; see for example (Karamadian 1977) and (Istrăţescu 1981).

Prehistory

To understand the prehistory of Brouwer's fixed point theorem one needs to pass through differential equations. At the end of the 19th century, the old problem[11] of the stability of the solar system returned into the focus of the mathematical community.[12] Its solution required new methods. As noted by Henri Poincaré, who worked on the three-body problem, there is no hope to find an exact solution: "Nothing is more proper to give us an idea of the hardness of the three-body problem, and generally of all problems of Dynamics where there is no uniform integral and the Bohlin series diverge."[13] He also noted that the search for an approximate solution is no more efficient: "the more we seek to obtain precise approximations, the more the result will diverge towards an increasing imprecision.".[14]

He studied a question analogous to that of the surface movement in a cup of coffee. What can we say, in general, about the trajectories on a surface animated by a constant flow?[15] Poincaré discovered that the answer can be found in what we now call the topological properties in the area containing the trajectory. If this area is compact, i.e. both closed and bounded, then the trajectory either becomes stationary, or it approaches a limit cycle.[16] Poincaré went further; if the area is of the same kind as a disk, as is the case for the cup of coffee, there must necessarily be a fixed point. This fixed point is invariant under all functions which associate to each point of the original surface its position after a short time interval t. If the area is a circular band, or if it is not closed,[17] then this is not necessarily the case.

To understand differential equations better, a new branch of mathematics was born. Poincaré called it analysis situs. The French Encyclopædia Universalis defines it as the branch which "treats the properties of an object that are invariant if it is deformed in any continuous way, without tearing".[18] In 1886, Poincaré proved a result that is equivalent to Brouwer's fixed-point theorem,[19] although the connection with the subject of this article was not yet apparent.[20] A little later, he developed one of the fundamental tools for better understanding the analysis situs, now known as the fundamental group or sometimes the Poincaré group.[21] This method can be used for a very compact proof of the theorem under discussion.

Poincaré's method was analogous to that of Émile Picard, a contemporary mathematician who generalized the Cauchy–Lipschitz theorem.[22] Picard's approach is based on a result that would later be formalised by another fixed-point theorem, named after Banach. Instead of the topological properties of the domain, this theorem uses the fact that the function in question is a contraction.

First proofs

At the dawn of the 20th century, the interest in analysis situs did not stay unnoticed. However, the necessity of a theorem equivalent to the one discussed in this article was not yet evident. Piers Bohl, a Latvian mathematician, applied topological methods to the study of differential equations.[23] In 1904 he proved the three-dimensional case of our theorem, but his publication was not noticed.[24]

It was Brouwer, finally, who gave the theorem its first patent of nobility. His goals were different from those of Poincaré. This mathematician was inspired by the foundations of mathematics, especially mathematical logic and topology. His initial interest lay in an attempt to solve Hilbert's fifth problem.[25] In 1909, during a voyage to Paris, he met Poincaré, Hadamard and Borel. The ensuing discussions convinced Brouwer of the importance of a better understanding of Euclidean spaces, and were the origin of a fruitful exchange of letters with Hadamard. For the next four years, he concentrated on the proof of certain great theorems on this question. In 1912 he proved the hairy ball theorem for the two-dimensional sphere, as well as the fact that every continuous map from the two-dimensional ball to itself has a fixed point.[26] These two results in themselves were not really new. As Hadamard observed, Poincaré had shown a theorem equivalent to the hairy ball theorem.[27] The revolutionary aspect of Brouwer's approach was his systematic use of recently developed tools such as homotopy, the underlying concept of the Poincaré group. In the following year, Hadamard generalised the theorem under discussion to an arbitrary finite dimension, but he employed different methods. H. Freudenthal comments on the respective roles as follows: "Compared to Brouwer's revolutionary methods, those of Hadamard were very traditional, but Hadamard's participation in the birth of Brouwer's ideas resembles that of a midwife more than that of a mere spectator.".[28]

Brouwer's approach yielded its fruits, and in 1912 he also found a proof that was valid for any finite dimension.,[29] as well as other key theorems such as the invariance of dimension.[30] In the context of this work, Brouwer also generalized the Jordan curve theorem to arbitrary dimension and established the properties connected with the degree of a continuous mapping.[31] This branch of mathematics, originally envisioned by Poincaré and developed by Brouwer, changed its name. In the 1930s, analysis situs became algebraic topology.[32]

Brouwer's celebrity is not exclusively due to his topological work. He was also the originator and zealous defender of a way of formalising mathematics that is known as intuitionism, which at the time made a stand against set theory.[33] While Brouwer preferred constructive proofs, ironically, the original proofs of his great topological theorems were not constructive,[34] and it took until 1967 for constructive proofs to be found.[35]

Reception

The theorem proved its worth in more than one way. During the 20th century numerous fixed-point theorems were developed, and even a branch of mathematics called fixed-point theory.[36] Brouwer's theorem is probably the most important.[37] It is also among the foundational theorems on the topology of topological manifolds and is often used to prove other important results such as the Jordan curve theorem.[38]

Besides the fixed-point theorems for more or less contracting functions, there are many that have emerged directly or indirectly from the result under discussion. A continuous map from a closed ball of Euclidean space to its boundary cannot be the identity on the boundary. Similarly, the Borsuk–Ulam theorem says that a continuous map from the n-dimensional sphere to Rn has a pair of antipodal points that are mapped to the same point. In the finite-dimensional case, the Lefschetz fixed-point theorem provided from 1926 a method for counting fixed points. In 1930, Brouwer's fixed-point theorem was generalized to Banach spaces.[39] This generalization is known as Schauder's fixed-point theorem, a result generalized further by S. Kakutani to multivalued functions.[40] One also meets the theorem and its variants outside topology. It can be used to prove the Hartman-Grobman theorem, which describes the qualitative behaviour of certain differential equations near certain equilibria. Similarly, Brouwer's theorem is used for the proof of the théorème de la variété centrale. The theorem can also be found in existence proofs for the solutions of certain partial differential equations.[41]

Other areas are also touched. In game theory, John Nash used the theorem to prove that in the game of Hex there is a winning strategy for white.[42] In economy, P. Bich explains that certain generalizations of the theorem show that its use is helpful for certain classical problems in game theory and generally for equilibria (Hotelling's law), financial equilibria and incomplete markets.[43]

Proof outlines

A proof using homology

The proof uses the observation that the boundary of D n is S n − 1, the (n − 1)-sphere.

The argument proceeds by contradiction, supposing that a continuous function f : D n → D n has no fixed point, and then attempting to derive an inconsistency, which proves that the function must in fact have a fixed point. For each x in D n, there is only one straight line that passes through f(x) and x, because it must be the case that f(x) and x are distinct by hypothesis (recall that f having no fixed points means that f(x) ≠ x). Following this line from f(x) through x leads to a point on S n − 1, denoted by F(x). This defines a continuous function F : D n → S n − 1, which is a special type of continuous function known as a retraction: every point of the codomain (in this case S n − 1) is a fixed point of the function.

Intuitively it seems unlikely that there could be a retraction of D n onto S n − 1, and in the case n = 1 it is obviously impossible because S 0 (i.e., the endpoints of the closed interval D 1) is not even connected. The case n = 2 is less obvious, but can be proven by using basic arguments involving the fundamental groups of the respective spaces: the retraction would induce an injective group homomorphism from the fundamental group of S 1 to that of D 2, but the first group is isomorphic to Z while the latter group is trivial, so this is impossible. The case n = 2 can also be proven by contradiction based on a theorem about non-vanishing vector fields.

For n > 2, however, proving the impossibility of the retraction is more difficult. One way is to make use of homology groups: the homology Hn − 1(D n) is trivial, while Hn − 1(S n − 1) is infinite cyclic. This shows that the retraction is impossible, because again the retraction would induce an injective group homomorphism from the latter to the former group.

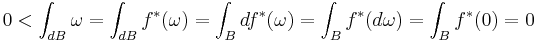

A proof using Stokes's theorem

To prove that a map has fixed points, one can assume that it is smooth, because if a map has no fixed points then convoluting it with a smooth function of sufficiently small support produced a smooth function with no fixed points. As in the proof using homology, one is reduced to proving that there is no smooth retraction f from the ball B onto its boundary dB. If ω is a volume form on the boundary then

giving a contradiction.

More generally, this shows that there is no smooth retraction from any non-empty smooth orientable compact manifold onto its boundary. The proof using Stokes's theorem is closely related to the proof using homology (or rather cohomology), because the form ω generates the de Rham cohomology group Hn−1(dB) used in the cohomology proof.

A combinatorial proof

There is also a more elementary combinatorial proof, whose main step consists in establishing Sperner's lemma in n dimensions.

A proof by Hirsch

There is also a quick proof, by Morris Hirsch, based on the impossibility of a differentiable retraction. The indirect proof starts by noting that the map f can be approximated by a smooth map retaining the property of not fixing a point; this can be done by using the Weierstrass approximation theorem, for example. One then defines a retraction as above which must now be differentiable. Such a retraction must have a non-singular value, by Sard's theorem, which is also non-singular for the restriction to the boundary (which is just the identity). Thus the inverse image would be a 1-manifold with boundary. The boundary would have to contain at least two end points, both of which would have to lie on the boundary of the original ball—which is impossible in a retraction.

Kellogg, Li, and Yorke turned Hirsch's proof into a constructive proof by observing that the retract is in fact defined everywhere except at the fixed points. For almost any point, q, on the boundary, (assuming it is not a fixed point) the one manifold with boundary mentioned above does exist and the only possibility is that it leads from q to a fixed point. It is an easy numerical task to follow such a path from q to the fixed point so the method is essentially constructive. Chow, Mallet-Paret, and Yorke gave a conceptually similar path-following version of the homotopy proof which extends to a wide variety of related problems.

A proof using the game hex

A quite different proof given by David Gale is based on the game of Hex. The basic theorem about Hex is that no game can end in a draw. This is equivalent to the Brouwer fixed-point theorem for dimension 2. By considering n-dimensional versions of Hex, one can prove in general that Brouwer's theorem is equivalent to the determinacy theorem for Hex.[44]

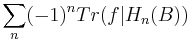

A proof using the Lefschetz fixed-point theorem

The Lefschetz fixed-point theorem says that if a continuous map f from a finite simplicial complex B to itself has only isolated fixed points, then the number of fixed points counted with multiplicities (which may be negative) is equal to the Lefschetz number

and in particular if the Lefschetz number is nonzero then f must have a fixed point. If B is a ball (or more generally is contractible) then the Lefschetz number is one because the only non-zero homology group is H0(B), so f has a fixed point.

A proof in a weak logical system

In reverse mathematics, Brouwer's theorem can be proved in the system WKL0, and conversely over the base system RCA0 Brouwer's theorem for a square implies the weak Konig's lemma, so this gives a precise description of the strength of Brouwer's theorem.

Generalizations

The Brouwer fixed-point theorem forms the starting point of a number of more general fixed-point theorems.

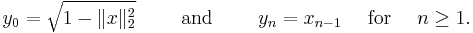

The straightforward generalization to infinite dimensions, i.e. using the unit ball of an arbitrary Hilbert space instead of Euclidean space, is not true. The main problem here is that the unit balls of infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces are not compact. For example, in the Hilbert space ℓ2 of square-summable real (or complex) sequences, consider the map f : ℓ2 → ℓ2 which sends a sequence (xn) from the closed unit ball of ℓ2 to the sequence (yn) defined by

It is not difficult to check that this map is continuous, has its image in the unit sphere of ℓ 2, but does not have a fixed point.

The generalizations of the Brouwer fixed-point theorem to infinite dimensional spaces therefore all include a compactness assumption of some sort, and in addition also often an assumption of convexity. See fixed-point theorems in infinite-dimensional spaces for a discussion of these theorems.

There is also finite-dimensional generalization to a larger class of spaces: If  is a product of finitely many chainable continua, then every continuous function

is a product of finitely many chainable continua, then every continuous function  has a fixed point,[45] where a chainable continuum is a (usually but in this case not necessarily metric) compact Hausdorff space of which every open cover has a finite open refinement

has a fixed point,[45] where a chainable continuum is a (usually but in this case not necessarily metric) compact Hausdorff space of which every open cover has a finite open refinement  , such that

, such that  if and only if

if and only if  . Examples of chainable continua include compact connected linearly ordered spaces and in particular closed intervals of real numbers.

. Examples of chainable continua include compact connected linearly ordered spaces and in particular closed intervals of real numbers.

The Kakutani fixed point theorem generalizes the Brouwer fixed-point theorem in a different direction: it stays in Rn, but considers upper semi-continuous correspondences (functions that assign to each point of the set a subset of the set). It also requires compactness and convexity of the set.

The Lefschetz fixed-point theorem applies to (almost) arbitrary compact topological spaces, and gives a condition in terms of singular homology that guarantees the existence of fixed points; this condition is trivially satisfied for any map in the case of D n.

See also

- Banach fixed-point theorem

- Schauder fixed-point theorem

- Tucker's lemma

- Kakutani fixed-point theorem

- Topological combinatorics

- Nash equilibrium

Notes

- ^ E.g. F & V Bayart Théorèmes du point fixe on Bibm@th.net

- ^ See page 15 of: D. Leborgne Calcul différentiel et géométrie Puf (1982) ISBN 2130374956

- ^ More exactly, according to Encyclopédie Universalis: Il en a démontré l'un des plus beaux théorèmes, le théorème du point fixe, dont les applications et généralisations, de la théorie des jeux aux équations différentielles, se sont révélées fondamentales. Luizen Brouwer by G. Sabbagh

- ^ D. Violette Applications du lemme de Sperner pour les triangles Bulletin AMQ, V. XLVI N° 4, (2006) p 17.

- ^ Page 15 of: D. Leborgne Calcul différentiel et géométrie Puf (1982) ISBN 2130374956.

- ^ This version follows directly from the previous one because every convex compact subset of a Euclidean space is homeomorphic to a closed ball. For details see convex set.

- ^ V. & F. Bayart Point fixe, et théorèmes du point fixe on Bibmath.net.

- ^ C. Minazzo K. Rider Théorèmes du Point Fixe et Applications aux Equations Différentielles Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis.

- ^ The interest of this anecdote rests in its intuitive and didactic character, but its accuracy is dubious. As the history section shows, the origin of the theorem is not Brouwer's work. More than 20 years earlier Henri Poincaré had proved an equivalent result, and 5 years before Brouwer P. Bohl had proved the three-dimensional case.

- ^ a b c Cette citation provient d'une émission de télévision : Archimède, Arte, 21 septembre 1999

- ^ See F. Brechenmacher L'identité algébrique d'une pratique portée par la discussion sur l'équation à l'aide de laquelle on détermine les inégalités séculaires des planètes CNRS Fédération de Recherche Mathématique du Nord-Pas-de-Calais

- ^ Henri Poincaré won the King of Sweden's mathematical competition in 1889 for his work on the related three-body problem: J. Tits Célébrations nationales 2004 Site du Ministère Culture et Communication

- ^ H. Poincaré Les méthodes nouvelles de la mécanique céleste T Gauthier-Villars, Vol 3 p 389 (1892) new edition Paris: Blanchard, 1987.

- ^ Quotation from H. Poincaré taken from: P. A. Miquel La catégorie de désordre, on the website of l'Association roumaine des chercheurs francophones en sciences humaines

- ^ This question was studied in: H. Poincaré Sur les courbes définies par les équations différentielles J. de Math. V 2 (1886)

- ^ This follows from the Poincaré–Bendixson theorem.

- ^ Multiplication by 1⁄2 on ]0, 1[2 has no fixed point.

- ^ "concerne les propriétés invariantes d’une figure lorsqu’on la déforme de manière continue quelconque, sans déchirure (par exemple, dans le cas de la déformation de la sphère, les propriétés corrélatives des objets tracés sur sa surface". From C. Houzel M. Paty Poincaré, Henri (1854–1912) Encyclopædia Universalis Albin Michel, Paris, 1999, p. 696-706

- ^ Poincaré's theorem is stated in: V. I. Istratescu Fixed Point Theory an Introduction Kluwer Academic Publishers (réédition de 2001) p 113 ISBN 1402003013

- ^ M.I. Voitsekhovskii Brouwer theorem Encyclopaedia of Mathematics ISBN 1402006098

- ^ J. Dieudonné, A History of Algebraic and differential Topology, 1900–1960, pages 17–24

- ^ See for example: E Picard Sur l'application des méthodes d'approximations successives à l'étude de certaines équations différentielles ordinaires Journal de Mathématiques p 217 (1893)

- ^ J. J. O'Connor E. F. Robertson Piers Bohl

- ^ A. D. Myskis I. M. Rabinovic The first proof of a fixed-point theorem for a continuous mapping of a sphere into itself, given by the Latvian mathematician P G Bohl (Russian) Uspekhi matematicheskikh nauk (NS) Vol 10 (N° 3) (65) (1955) pp 188–192

- ^ J. J. O'Connor E. F. Robertson Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer

- ^ H. Freudenthal The cradle of modern topology, according to Brouwer's inedita Hist. Math. 2 p 495 (1975)

- ^ Freudenthal explains: "... cette dernière propriété, bien que sous des hypothèses plus grossières, ait été démontré par H. Poincaré" H. Freudenthal The cradle of modern topology, according to Brouwer's inedita Hist. Math. 2 p 495 (1975)

- ^ H. Freudenthal The cradle of modern topology, according to Brouwer's inedita Hist. Math. 2 p 501 (1975)

- ^ L. E. J. Brouwer Über Abbildungen von Mannigfaltigkeiten Mathematische Annalen 71, pp. 97–115 (1912)

- ^ If an open subset of a manifold is homeomorphic to an open subset of a Euclidean space of dimension n, and if p is a positive integer other than n, then the open set is never homeomorphic to an open subset of a Euclidean space of dimension p.

- ^ J. J. O'Connor E. F. Robertson Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer.

- ^ The term algebraic topology first appeared 1931 under the pen of David van Dantzig: J. Miller Topological algebra on the site Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (2007)

- ^ Later it would be shown that the formalism that was combatted by Brouwer can also serve to formalise intuitionism. For further details see intuitionistic logic.

- ^ For a long explanation, see: J.P. DubucsL.J.E. Brouwer : Topologie et constructivisme Revue d’histoire des sciences V. 41 N°41-2 pp 133–155 (1988)

- ^ H. Scarf found the first algorithmic proof: M.I. Voitsekhovskii Brouwer theorem Encyclopaedia of Mathematics ISBN 1402006098.

- ^ V. I. Istratescu Fixed Point Theory. An Introduction Kluwer Academic Publishers (new edition 2001) ISBN 1402003013.

- ^ "... Brouwer's fixed point theorem, perhaps the most important fixed point theorem." p xiii V. I. Istratescu Fixed Point Theory an Introduction Kluwer Academic Publishers (new edition 2001) ISBN 1402003013.

- ^ E.g.: S. Greenwood J. Cao Brouwer’s Fixed Point Theorem and the Jordan Curve Theorem University of Auckland, New Zealand.

- ^ J. Schauder Der Fixpunktsatz in Funktionalraumen Studia. Math. 2 (1930) pp 171–180

- ^ S. Kakutani A generalization of Brouwer’s Fixed Point Theorem Duke Math. Journal 8 (1941) pp 457–459

- ^ These examples are taken from: F. Boyer Théorèmes de point fixe et applications CMI Université Paul Cézanne (2008–2009)

- ^ For context and references see the article Hex (board game).

- ^ P. Bich Une extension discontinue du théorème du point fixe de Schauder, et quelques applications en économie Institut Henri Poincaré, Paris (2007)

- ^ David Gale (1979). "The Game of Hex and Brouwer Fixed-Point Theorem". The American Mathematical Monthly 86 (10): 818–827. doi:10.2307/2320146. JSTOR 2320146.

- ^ Eldon Dyer (1956). "A fixed point theorem". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 7 (4): 662–672. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1956-0078693-4. http://www.ams.org/journals/proc/1956-007-04/S0002-9939-1956-0078693-4/home.html.

References

- Sobolev, V. I. (2001), "Brouwer theorem", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=B/b017670

- Gale, D. (1979). "The Game of Hex and Brouwer Fixed-Point Theorem". The American Mathematical Monthly 86 (10): 818–827. doi:10.2307/2320146. JSTOR 2320146.

- Morris W. Hirsch, "Differential Topology", Springer, 1980 (see p. 72–73 for Hirsch's proof utilizing non-existence of a differentiable retraction)

- S. N. Chow, J. Mallet-Paret and J. A. Yorke, Finding zeroes of maps: Homotopy methods that are constructive with probability one, Math. of Comp. 32 (1978), 887–899.

- R. B. Kellogg, T. Y. Li and J. A. Yorke, A constructive proof of the Brouwer fixed point theorem and computational results, SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 13 (1976), 473–383.

- S. Karamadian (ed.), Fixed points. Algorithms and applications, Academic Press, 1977

- V.I. Istrăţescu, Fixed point theory, Reidel, 1981

External links

- Brouwer's Fixed Point Theorem for Triangles at cut-the-knot

- Brouwer theorem, from PlanetMath with attached proof.

- Reconstructing Brouwer at MathPages